In a past life I was an astrophysicist

An astrophysicist uses mathematics and computation to make inferences and test hypotheses about how the universe works. An astrophysicist might study how stars move, how stars are borns, or how they die. They could study giant molecular clouds or black holes or galactic mergers. Even as an astrophysicist myself, I find that the majority of the field remains largely inaccesible because of how specialized each area of research is.

There is a common misconception that astronomy and astrophysics are interchangeable, one in the same. I see astronomy as the deceptively broad catagory of science of all things outside of our world, the study of what the universe is like. Astrophysics, on the other hand, is the study of how the universe works. But even within this category, astrophysicists have incredibly diverse disciplines. With four astrophysicists in a room, one may study planets, another stars, and the other two study black holes but one focuses on the radiation emitted from ancient active galactic nuclei and the other the theoretical implications of warped space-time. In essence, despite having the same disciplinary title, it's entirely possible each of these four astrophysicists would have no idea what the others are talking about. Such is life in the hyper-specialized world of science.

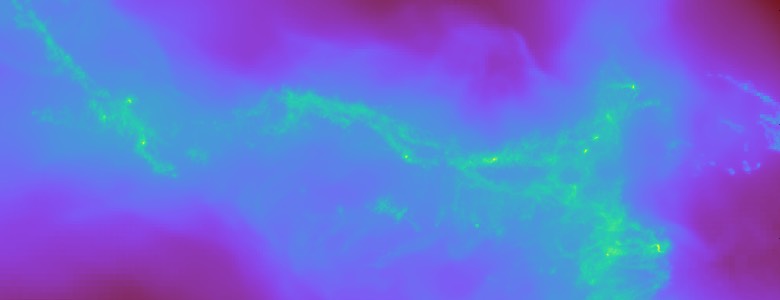

My specialty is the computational modeling of the formation of star clusters. Stars all form from the collapse of gas in a giant molecular cloud (GMC). The vast maojrity of stars also form in clusters, spatially compact systems where hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of stars closely interact gravitationally with one another. So where does my work come in? Why are computational models necessary to study this? Observing star cluster formation is notoriously difficult. The process of GMC collapse, the formation of individual stars, and the hierarchical assembly of the star cluster takes place over hundreds of thousands or millions of years. The nearest regions of star cluster formation are not only many thousands of lightyears away, but they also tend to reside deep within GMC structures which block our ability to watch the formation of the embedded clusters. But, we are able to observe star clusters that have successfully formed and cleared their surroundings of dense obscuring gas. Therefore we know what the star cluster formation process results in, but it is currently unknown how that processs gets to the point of completion. It is my job as a computational astrophysicist to help find out how star cluster formation works. This is a particularly difficult task since the star formation process is incredibly complex. Such simulation require detailed magnetohydrodynamics, realistic heating and cooling of gas, gravitational interactions between stars and stars and gas, and radiative and both radiative and mechanical feedback mechanisms from massive stars (ionizing radiation, stellar winds, and supernovae).

New Perspectives on the Formation and Early Evolution of Stellar Clusters

My thesis is two-fold. First, I test the hypothesis that the timing of massive star formation has significant effects on the star cluster formation process. Specifically, that early-forming massive stars supress subsequent star formation and stifles the hierarchical cluster assembly process. Secondly, I have built a revolutionary tool which bridges two types of hydrodynamical data structures: Voronoi meshes and adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) grids. This tool allows output data from Voronoi mesh codes (which excel at simulating rotating gas and particle structures such as galaxies) to be converted into input data for AMR codes (which are faster and more capable at resolving intense shocks). My tool can ultimately be used to bridge the gap between galaxy simulations and detailed simulations of individual star forming regions, a feat which is computationally impossible to achieve with any single simulation.

Other than astrophysics, my endeavors as a Ph.D. candidate have also resulted in several computer science projects of which I am particularly proud. I built a parallel processing Python library that utilizes MPI packages to allow for more efficient task-based parallel processing rather than the slower data-based processing. From scratch, using only numpy Python libraries, I built a customizable L-layer neural network with any number n neurons per layer. I have also amassed an enormous array of data visualization routines, some taking advantage of my parallel processing library, and others utilizing other visualization-specific packages to generate images fit for presentations at conferences such as the American Astronomical Society (AAS-233, AAS-236) at which I received the Chambliss Astronomy Achievement Graduate Student Honorable Mention for my poster presentation.